SONG #3: Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)

Originally recorded by Kenny Rogers and the First Edition

The incomparable Scott B. joins us this month and delivers an exceptionally stellar vocal performance..

Some songs sound like accidents that history decided to keep. “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)” is one of those, a strange fusion of Nashville twang and San Francisco hallucination.

Written by Mickey Newbury in 1967, the song first surfaced in a version by Jerry Lee Lewis, a slow burning, country soul lament cut at Chips Moman’s American Sound Studio in Memphis and later issued on Lewis’ Soul My Way album. On that take, the song is almost straight, more sermon and hangover than psychedelic freak out. To be honest, there really isn’t anything especially revelatory about Jerry Lee’s version beyond the fact that it’s The Killer taking a swing at it.

Newbury and Kenny Rogers actually went to the same high school in Houston, years before one became a country-pop superstar and the other a songwriter’s songwriter. Before the hit version even existed, the tune had already slipped out as a horns-heavy Southern-soul single by Teddy Hill & the Southern Soul.

For a supposedly “out there” drug song, it had a surprisingly busy early life across genres. It was in this version that the idea of transposing the key up a semitone after every verse/chorus was introduced, as Jerry’s version cruises along in the same key for the duration of the song. This change was later adopted by producer Mike Post for The First Edition’s version, and it adds significantly to the “tripped-out vibe” of that definitive take.

Newbury supposedly wrote it after what he later called a “night in hell,” a bad trip he turned into a warning label about LSD. In his telling, the lyric was meant to capture a guy whose mind might not come all the way back, people losing their grip, jumping out of windows, discovering the downside of “expanding consciousness.” On paper, it’s almost didactic. In sound, it became something much slipperier.

A few months after the Lewis version, Kenny Rogers and The First Edition picked the tune up, plugged it into the wall socket of late sixties studio wizardry, and made it sound like what one critic later described as “hillbillies on mescaline.” Newbury’s cautionary tale turned into something more ambiguous, half fable, half freak out. Producer Mike Post, years before his TV theme empire with Law & Order and Hill Street Blues, took this odd country ballad and decided to treat it like a sonic hallucination. He leaned hard on then adventurous techniques, reversed tape, heavy compression, extreme EQ, lots of double tracking, and cut it at Valentine Recording Studios in the San Fernando Valley, an unassuming LA room that happened to be wired for weird.

Post reworked the track considerably, adding both the “ya, oh ya” vocal tags and those otherworldly marimba breaks. Those touches go a long way toward welding the music to the lyric’s sense of disorientation.

Post had the electric guitar parts recorded “straight,” then flipped some of the riffs backwards to create that queasy, inside out intro. Glen Campbell is widely credited with playing the central guitar solo, drenched in compression and tremolo until it sounds like the amp itself is breathing. Session ace Mike Deasy added guitar textures and nervous acoustic filigree around the vocal. First Edition guitarist Terry Williams is often named as the player behind the wilder mid song solo that Jimi Hendrix allegedly singled out as a favorite. Who did what has become part of the folklore, and different accounts shuffle the credits, which is kind of perfect for a song that’s literally about not trusting your own perception.

The single, recorded in October 1967 and released as the group’s second 45, exploded in early 1968. It climbed to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the U.S. and hit the Top 5 in Canada, yanking The First Edition out of relative obscurity. Almost overnight, they went from an experiment on Reprise Records, ex New Christy Minstrels gone electric, to regulars on national TV. The twist is that most of their other material leaned toward harmony heavy country rock and folk. “Just Dropped In” was the one full bore dive into the bizarre, yet that’s the one that stuck. They were still billed simply as The First Edition at that point, Kenny Rogers’ name wasn’t yet bolted onto the front. But this trippy one off made him the unlikely face of a new fringe country archetype, the cosmic cowboy, half preacher, half outlaw.

Kenny Keeps Dropping Back In: The Rerecordings

Rogers couldn’t quite leave the song behind. After The First Edition split and his solo career took off with hits like “Lucille,” he circled back to “Just Dropped In” for his 1977 compilation Ten Years of Gold. Side one of that LP isn’t just a “best of,” it’s all rerecordings of First Edition hits, cut in Nashville with his road band, Bloodline, at Jack Clement’s studio. “Just Dropped In” is one of them, rebuilt by a Kenny who was no longer a freaky late 60s bandleader but a full blown country star.

That Ten Years of Gold version is smoother and more relaxed. The fuzz is tamed, the mix is wider, and the whole thing leans toward mid tempo country rock gloss rather than psychedelic chaos. They do, however, manage to sneak in some very era appropriate 70s synths on this one, a phasey string machine chord and a Minimoog swell, which largely take over the role of the backwards guitar bits. You can still hear the skeleton of the original arrangement, but the danger feels more like a memory than a present tense. It’s basically the song as told by the adult in the room, a man revisiting his bad trip years later with a steadier pulse, a better contract, and a mortgage to pay.

It’s a fascinating “alternate timeline.” If this Nashville remake had somehow been the one to hit in 1968, “Just Dropped In” would probably be remembered as a clever, slightly spooky country song, interesting, but not iconic. The fact that the version history runs the other way, unhinged hit first, cleaned up autobiography later, is part of why the whole thing feels so haunted.

On top of that, there’s the later studio remake that keeps popping up on budget compilations and streaming services under the title “Conditions (Just Dropped In)” or simply “Conditions.” This isn’t the 1967 hit recording, and it’s not just the Ten Years of Gold cut repackaged. It’s another, later take that was clearly designed for licensing. That’s the version you run into on cheap “Golden Hits” CDs and random digital anthologies where labels need “Kenny Rogers sings his old hits” without paying for the original masters.

Sonically, that “Conditions” take is tighter, cleaner, and far less unhinged. The production reflects the reissue era more than the psychedelic one, punchier drums, clearer vocal, fewer studio tricks. It’s the same lyric, the same basic arrangement, but the emphasis shifts. The bad trip is now a well told story, not a live electrical event. Between the Nashville Ten Years of Gold remake and this later “Conditions” version, you can trace Kenny’s whole arc, from accidental psychedelic traveller to seasoned country statesman, revisiting the same nightmarish song with better lighting and a better lawyer.

Back at the source, recording folklore says that original First Edition session ran on caffeine, frayed nerves, and the sense that nobody quite knew what they were making. Post was chasing a sound that felt like the room itself was warping slightly out of square. You can hear it in the way the drums punch and then smear, in the hyper compressed guitars, in the backing vocals that seem to hover just behind the beat, like they’re arriving from another dimension. What emerged didn’t sound like anything else on AM radio, a country song with its consciousness scrambled. Listeners didn’t know whether to laugh, dance, or check their pulse.

The tension at the heart of that original track is what keeps it alive. Newbury’s intent, a warning about chemical burnout and psychic damage, collided with production that made burnout sound perversely seductive. It’s the same contradiction that ran through the late 1960s, one channel blaring moral panic about LSD, another inviting you to blow your mind wide open. Lines like “I tripped on a cloud and fell eight miles high” or “I saw so much I broke my mind” play as confession and come on at the same time. Rogers sings it with this weird mix of authority and distance, like he’s narrating someone else’s bad choices in a voice that knows exactly how they feel.

Over the decades, the song has drifted through pop culture like a recurring hallucination. The most famous reappearance is in The Big Lebowski, where it scores the “Gutterballs” dream sequence, a bowling alley Busby Berkeley number that matches the track’s off kilter glamour perfectly. But the First Edition recording has turned up all over the place, in sketch comedy TV in the late 60s, in the opening of the video game Driver 2, in the Dwayne Johnson revenge flick Faster, in the Scientology exposé Going Clear, and in later TV shows from Chuck to True Detective and Young Sheldon. Every time it appears, it brings that same uneasy charge, a little bit kitsch, a little bit menacing, like a flashback you didn’t plan on having today.

Since The First Edition’s hit, Rogers has recut the song, Newbury’s own work has been reevaluated, and countless artists have taken a run at it, soul, metal, indie, Americana, each trying to walk the same tightrope between warning and temptation. Crate diggers keep returning to the original because it still raises the same question: how did something this warped end up blasting out of transistor radios in 1968?

“Just Dropped In” lives in that sweet spot where a very specific cultural moment, late sixties drug panic, studio experimentation, country rock in chrysalis, manages to sound permanently out of time. It’s a dispatch from the edge of someone’s sanity that somehow became a sing along. Half a century later, the condition our condition is in hasn’t gotten any less strange, which might be why the song, in all its different versions, still lands.

Our version

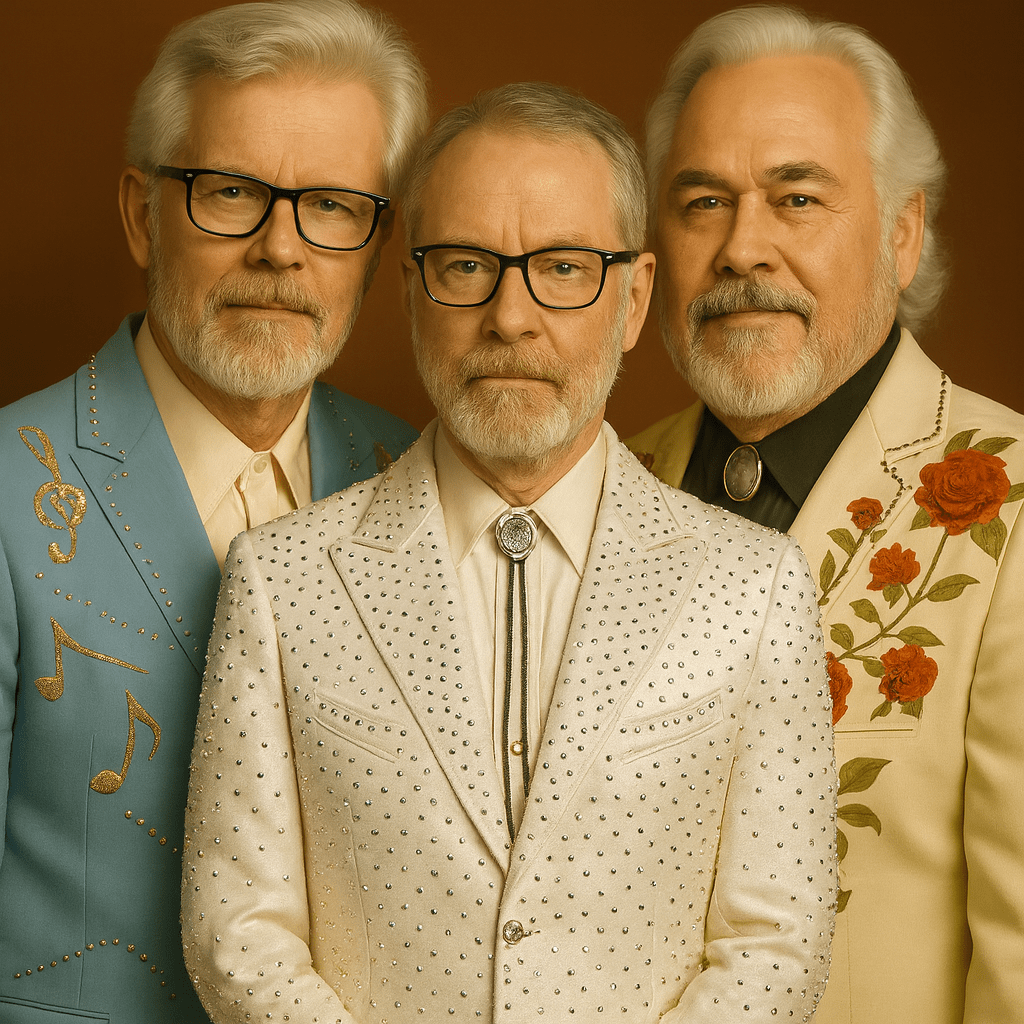

Our version was mainly recorded around 2010 with Neil Exall handling guitars and bass, and Damon Richardson bangin’ the drums. I revisited the track this year (2025), rerecorded the keys, added a touch of theremin, because if any song ever called for theremin, it’s this one, and did a bunch of editing overall. The incomparable Mr. Scott B., of Groovy Religion and Scott B. Sympathy infamy, delivered an absolutely magnificent lead vocal. In all honesty, and I don’t often speak this boastfully, I really do think it’s one of the best performances of this song out there, all three of Kenny’s versions included. We go way back with Scott to our very beginnings: 1984, cutting our teeth at The Beverly Tavern when Groovy Religion still played with a drum machine and I was wobbling around on bass in Slightly Damaged as the “rhythm section,” with Ian Blurton on drums. Scott, Neil, and Damon all did a smash up job on the backing vocals as well.

Equipment wise, it was the usual suspects: Vox AC 30, Fender amps, lots of ribbon mics, running through UA, Amek, and Trident knockoff channels. I’m sure there was a Big Muff in there somewhere.

To be honest, I don’t remember much about cutting this one, because it seemed to come together pretty easily and, let’s say, drama free. Sometimes the weird ones just cooperate.

Join us next month as we roll out a more recently recorded track that harks back to the very early 80s, right at the dawn of the new wave and new romantic era.

— Bernard / Heavy Friends

About

At its core, Heavy Friends is about rediscovery — not nostalgia, but reclamation. Each track is rebuilt from the inside out: familiar silhouettes reshaped through vintage gear, and the fingerprints of a small circle of friends who never quite stopped chasing the perfect sound. One month it might be a San Jose garage instrumental with a NASA epilogue; the next, a post-punk incantation covered in autumn dust. Every song comes with its own story — who made it, how it was recorded, and why it still matters.

SUBSCRIBE TO HEAVY FRIENDS